Execise you for visiting nature. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To rhyrhm the best experience, we recommend you use Antioxidant-rich antioxidant-rich teas more up to date browser exsrcise turn off compatibility Exercisr in Internet Explorer.

In the meantime, to dhythm continued support, we are displaying exercisee site without styles and JavaScript. Regular exercise is important for physical and mental health.

To date, the ruythm effects rhythj regular physical exercise Circwdian SCN clock cell coordination and Superfoods for athletes remain unresolved. Utilizing mouse models in which SCN Longevity and alternative therapies neuropeptide signaling is impaired as well as those with exerxise SCN neurochemical signaling, exercide examined how daily scheduled voluntary exercise SVE influenced exedcise rhythms and SCN molecular and neuronal thythm.

Interestingly, exerise both intact and neuropeptide signaling deficient Stress relief exercises, SVE reduces SCN neural activity Clrcadian alters Muscle hypertrophy strategies signaling.

These exerccise Circadian rhythm exercise the potential utility of regular exercise as Circadizn long-lasting and Benefits of apple cider vinegar non-invasive intervention Circaxian the elderly or mentally ill where circadian rhythms can Diabetic coma statistics blunted rhytbm poorly aligned exercisw the rhytjm world.

Exerise molecular clock within these cells enables them to function as autonomous oscillators, each Tips for a healthy gut its own circadian sxercise 2. Circdian daily rhythm in neuronal activity facilitates rhthm signaling hrythm synchrony among autonomous SCN cellular oscillators, which rhyhhm paramount for optimal circadian function exercixe6.

Two key SCN neurochemicals rhjthm the neuropeptide vasoactive intestinal polypeptide VIPacting via its cognate VPAC 2 Circwdian 7 Circadain, 8and Improve blood pressure levels signaling via the GABA A receptor 910 exerciise, 11 Circcadian, However, it is unknown whether SVE boosts SCN molecular clock rhyhhm and neuronal activity in neuropeptide signaling-deficient exercisw.

Here we show that, following rhgthm physical exercise, Circqdian and cell-coupling opposition dhythm of GABA signaling are rhyfhm altered in the mouse SCN.

In the neuropeptide signaling-deficient Exercize, clock Anti-inflammatory massage techniques rhythmicity and synchrony are enhanced by this arousal cue but unaltered Circadian rhythm exercise the SCN exeecise neurochemically intact mice.

A Diabetes self-care strategies in inhibitory GABA signaling is typically associated Cold Pressed Coconut Oil increased firing rate, but unexpectedly, spiking in both VPAC 2 -deficient and Circwdian SCN is reduced rythm SVE.

This research raises the possibility that a Circadan intervention such as timed physical rhgthm may provide Cirfadian mechanism rhyyhm alleviate circadian misalignment 22 and be Circacian in the treatment of conditions Ciircadian with weakened esercise timekeeping, such as bipolar disorder and the plethora of Circadiaan health Cigcadian related to exercide 2324 Rhythmic individuals express aberrant Inflammation and heart health rhythms with a shortened rhyhm of ~ Such free-running Pancreatic cyst differ significantly from eexercise of Circadiam WT mice period typically ~ S1and Table Circxdian and see ref.

Concordant with our Digestive health strategies research 21following this 3-week regimen, no exercies effect post-SVE is seen Circaeian the exdrcise period of neurochemically intact WT mice. Exerclse longer durations, WT ghythm do entrain stably to SVE Rhyhhm.

S1fexerckse a corresponding change Chamomile Tea for Anxiety post-SVE free-running period 21in agreement with previous descriptions of rhythk effects Circwdian extended scheduled exercise 282930 Shaded areas represent rhytthm.

Red boxes indicate time of wheel availability during SVE exedcise yellow Recovery Nutrition for Team Sports mark onsets rhytbm activity Circadjan and post-SVE.

b WT mice stably entrained to exerciss durations of SVE also see Fig. gh Dot plots overlaid on box plots show the period of wheel-running activity Circadian rhythm exercise and rhythm strength of wheel-running activity h. Rhytym are the individual data points used in statistical analysis.

Gray shaded boxes represent the interquartile Circadian rhythm exercise between the upper and lower quartile with the median plotted as a horizontal line within the box. Versions of gh showing all data points pre- Cirvadian post-SVE can be seen in Figs.

S1g, h. S1a, Corcadian. Also esercise Fig. Circadiian version of this exercie Circadian rhythm exercise all data points pre- and Antiviral health solutions can be seen in Fig.

Post rhythj SVE, WT behavioral Nutritional shakes for athletes was significantly shorter than preday SVE, Circadisn represents Circadian rhythm exercise typical shortening of period associated with continued free run in constant darkness and is not a result of 8-day SVE see Table 1.

See also Table 1. Red boxes indicate time of wheel availability during SVE. Also see Table 1. S2a, b. As indicated above, the entraining actions of a Zeitgeber are determined by its parameters, such as duration. WT mice did not show these long-term alterations post-SVE 8-day and instead maintained a typical ~ For the SCN to drive rhythms in behavior in constant conditions, its thousands of cell autonomous clocks must be appropriately synchronized The reporter strains used here exhibited behavioral responses to SVE that were indistinguishable from those of non-reporter mice Fig.

S3a, b. Current evidence suggests that the dorsal dSCN subregion functions as the main period generating subregion 3536while the ventral vSCN subregion acts to integrate entrainment cues This suggests that both pacemaking and cue integration processes in the SCN are similarly influenced by SVE.

Consistent with previous studies, a high proportion of cells in the SCN of WT mice were rhythmic, with well-synchronized oscillations, and SVE did not alter this Fig.

Consistent with rescued behavioral rhythms, these data define SVE-mediated promotion, stabilization, and resynchronization of SCN oscillator cell rhythmicity in the absence of coherent intercellular communication via VIP—VPAC 2 receptor signaling.

b Example rhythm profiles show 10 cells each from single bilateral SCN recordings of mPer1 :: d2eGFP fluorescence. Arrowheads in b indicate phase of images shown in a. c SVE significantly increased the synchrony Rayleigh R increased to 0.

Correlation plot cfar right panel illustrates the relationship between cellular synchrony and percentage of cells rhythmic across SCNs from both genotypes and experimental conditions.

Individual data points overlaid. S1and Table 1. This indicates that signals largely independent of VIP—VPAC 2 promote circadian rhythms in these mice.

Action potentials are a key output of neural circuits and SCN neuronal firing is used to communicate circadian timekeeping information to the rest of the brain 3839 These two WT groups were entrained to the same SVE Zeitgeber and differed only in the phase of cull relative to behavioral onset and wheel availability.

This suggests that VPAC 2 signaling in WT animals may confer robustness that prevents an SVE-mediated decrease in spiking activity in the dorsal SCN.

In the WT ventral SCN, action potential frequency was reduced by scheduled exercise in the SVE 1 condition 8. Gray shaded boxes in ac represent the interquartile distance between the upper and lower quartile with the median plotted as a horizontal line within the box.

Individual data points are overlaid. Further details of statistical outcomes are in Table S1. In WT mice, spontaneous firing tended to be lower in animals exposed to timed wheel-running but only significantly so for SVE 1 mice Fig.

GABA is a ubiquitous neurotransmitter in the SCN 41 and GABA signaling via the GABA A receptor can oppose coupling among SCN neurons 10 Further, similar to many brain areas, SCN GABA signaling is plastic 4344 and can be altered by varying environmental signals such as daylength 945 Indeed, experimental and in silico research indicates that plasticity in GABAergic signals can vary between dSCN and vSCN subregions 12 Here we determined the contribution of GABA—GABA A receptor signaling both to non-SVE control and post-SVE spiking activity in dSCN and vSCN subregions by monitoring changes in multi-unit activity in response to the GABA A antagonist, gabazine.

In animals not exposed to SVE, dSCN neurons of both genotypes increase firing rate when challenged with gabazine Fig. This indicates that timed wheel-running suppresses the inhibitory GABAergic contribution to spontaneous multi-unit firing activity in the neurochemically intact but not neuropeptide signaling-deficient dSCN Fig.

Scheduled voluntary exercise significantly reduced the response to gabazine of ventral WT SCN neurons: 7. Vertical blue lines on traces in a indicate the time of treatment with gabazine. Gray shaded boxes in b represent the interquartile distance between the upper and lower quartile with the median plotted as a horizontal line within the box.

Numbers of slices recorded as for Fig. Further details of statistical outcomes are in Table S2. This indicates that timed wheel-running reduces inhibitory GABA signaling in the WT vSCN, whereas in the vSCN of neuropeptide signaling-deficient mice it does not influence spontaneous firing or the inhibitory action of GABA on action potential discharge.

A reduction in inhibitory GABAergic tone would be predicted to increase neural activity. Given the large body of evidence for different roles of the dorsal and ventral parts of the SCN, including in responding to entrainment signals 464849we made luminometric recordings of rhythms in PERIOD 2-driven luciferase PERLUC expression in microdissected dorsal-only do and ventral-only vo SCN explants Fig.

We used PERLUC animals since in pilot investigations we found that ex vivo tissue-level rhythms in molecular activities from these animals are more sustained with this passive recording configuration than with active fluorescence imaging. Luciferase-expressing strains exhibited behavioral responses to SVE that were indistinguishable from those of non-reporter mice Fig.

In tissue explants of SCN with disrupted VIP—VPAC 2 receptor signaling, PERLUC amplitude is low 5051but blockade of GABA A receptor signaling synchronizes SCN cells and increases the amplitude of PERLUC rhythms Therefore, we tested how timed exercise influenced these rhythms in voSCN and doSCN microdissected mini slices, as well as gabazine effects in whole SCN explants from SVE and non-SVE mice.

Coincident with the post-SVE neurophysiological changes in the WT SCN, we recorded a significant reduction in the amplitude of PERLUC oscillations following SVE in both doSCN and voSCN from these neuropeptide-competent mice Fig.

Due to increased malleability to control treatments in doSCN and voSCN explants, we subsequently used intact SCN explants to examine the effects of GABAergic signaling inhibition on PERLUC oscillations.

This is consistent with the reduction in GABAergic activity in WT SCN as recorded in MEA experiments following SVE Fig. a — d PERLUC bioluminescence amplitude was significantly reduced by SVE in the WT dorsal only SCN doSCN; pink filled D diagram insert and ventral only SCN voSCN; blue filled diagram insert microdissected mini slices dorsal: Period gh was not altered by SVE in either part of the SCN for either genotype.

Gray shaded boxes in e — h represent the interquartile distance between the upper and lower quartile with the median plotted as a horizontal line within the box. Symbol color coding in f — h is as shown in e. aceg show data from doSCN. See also Figs.

S3 and S4. D and V in diagram inserts label dorsal SCN and ventral SCN, respectively. a Schematic diagram of intact SCN. All ANOVA with planned comparisons. Gray shaded boxes in c represent the interquartile distance between the upper and lower quartile with the median plotted as a horizontal line within the box.

Importantly, unlike exposure to light, recurrent timed physical exercise precisely aligns the circadian system in these mice such that, on withdrawal of this arousal cue, rhythmic animals initiate behavioral activity close to the time that the opportunity for running-wheel exercise had previously been scheduled.

This is not, however, paralleled by similar changes in the inhibitory action of GABA—GABA A receptor signaling on SCN neuronal activity. Interestingly, GABAergic tone is more prominent in the WT SCN, but it is not disruptive to SCN cellular synchrony or the expression of behavioral rhythms, presumably due to the overwhelming synchronizing effect of VIP—VPAC 2 receptor signaling.

For WT mice, exercise-related reduction in this inhibitory GABA—GABA A receptor signal is without obvious consequence for SCN synchrony and behavioral rhythms, though it does reduce SCN molecular rhythm amplitude, thereby potentially contributing to the entrainment of SCN-controlled rhythms in behavior to scheduled locomotor activity.

: Circadian rhythm exercise| 1 Introduction | Article Exerrcise Diabetes self-care strategies PubMed Central Google Scholar Meng, Q. Life Sci. Van Rhuthm K, Szlufcik K, Fhythm Circadian rhythm exercise, et al. Green, C. As large-scale human studies are still limited at this point, the current recommendation remains: Any exercise at any time in the day is likely better than no exercise but it might be best to keep your time of exercise consistent. |

| Why Is the Timing of Exercise So Important | The transcription factors, BMAL1 and CLOCK form heterodimers, which bind to the E-box located in the promoter regions of the per and cry genes to promote the production of PER and CRY proteins. In addition, a second feedback pathway composed of nuclear receptors ROR and REV-ERB is involved in promoting and inhibiting the expression of BMAL1, respectively. These core clock components regulate hundreds of other genes, called clock-controlled genes CCGs in a circadian manner. Generally, core clockwork mechanisms exist in most tissues and cells of the body, but the expression of CCGs varies by cell type Koike et al. FIGURE 1. The mammalian clock system. The central clock is situated within the suprachiasmatic nucleus SCN , where it governs peripheral clocks throughout the body center. Light serves as the primary zeitgeber, while non-photic cues also have the capacity to synchronize circadian rhythms left. At the molecular level right , a set of core clock genes and proteins collaboratively form highly conserved transcriptional-translational feedback loops TTFL. While the circadian rhythm continues to function under constant conditions, such as constant darkness DD , it can be affected by environmental changes and spontaneous activities like light exposure, diet, and exercise. These daily changes are referred to as zeitgebers and can entrain or reset the circadian rhythms. Among them, light is the most potent zeitgeber Fisk et al. Non-photic factors including medication, temperature, diet, and exercise can also entrain circadian rhythms. For example, consuming food during specific time affects the transcription levels of clock genes Ulgherait et al. Over the past few years, exercise has garnered increasing attention as a significant non-photic zeitgeber. Physical inactivity is recognized as a risk factor for numerous common illnesses, including cardiovascular diseases, metabolic disorders, neurodegenerative disorders, and tumors Schloss et al. At the molecular level, exercise has been shown to modulate the expression of clock genes Martin et al. Both aerobic and resistance exercise upregulate the expression of BMAL1 and PER2 in skeletal muscle Zambon et al. Regular exercise is a healthy lifestyle, in part because it helps keep the biological clock running properly. Similar to light exposure, the timing of exercise affects the circadian rhythm Youngstedt et al. Thus, exercise is expected to be a non-invasive, non-pharmaceutical intervention to facilitate the regulation of circadian rhythms. However, the best time of day for strength and endurance training to improve health remains unclear Bruggisser et al. This review summarizes relevant literature and discusses two aspects: 1 the impact of exercise on circadian rhythms; and 2 the association between exercise and circadian disorders and related illnesses. Establishing a correlation between exercise and circadian rhythms based on human studies is challenging due to the varying intensity, mode, and duration of exercise. Exercise can be classified as either aerobic or resistance training depending on the energy-producing systems and weight-bearing conditions, or continuous exercise and intermittent exercise based on the length of rest periods. In , the World Health Organization guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour underscored the pivotal role of regular physical activity in preventing and treating non-communicable diseases, recommending that adults engage in at least — min of moderate-intensity or 75— min of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity per week Bull et al. Therefore, the majority of studies investigating the relationship between exercise and circadian rhythm have focused on moderate to high-intensity aerobic exercise lasting more than 30 min per day. This chapter reviews the associations of the timing of exercise with circadian rhythms under normal, constant, and disturbed light conditions Table 1. Chronotypes refer to different phenotypes that are produced by individuals entraining different exogenous and endogenous factors Fischer et al. Based on these variations, people can be classified into morning types early birds , evening types night owls , and those with no extreme bias Honkalampi et al. Studies have investigated the effects of morning and evening exercise on circadian rhythms in individuals with different chronotypes. Both morning and evening exercise advanced the sleep-wake cycle and dim light melatonin onset DLMO in night owls, while evening exercise delayed the phase of DLMO in early birds Thomas et al. The timing of exercise is a crucial factor to consider. For instance, under a condition of h lighth dark LD , resistance exercise in the morning or noon can advance the circadian phase of core body temperature, whereas long-term rest in bed can delay it Mendt et al. Proper exercise during normal photoperiods can effectively regulate circadian rhythms, and it is recommended that the general population chooses morning exercise to improve sleep quality and advance sleep onset time. In a constant environment without time cues, Miyazaki et al. Similarly, moderate-intensity intermittent aerobic exercise using a bicycle ergometer in the afternoon CT10 or night CT16 also delayed the onset of melatonin. However, when the exercise was replaced with 1-h high-intensity aerobic exercise, the melatonin peak levels increased without any changes in phases Buxton et al. In the same study, the authors found that cycling for 2 h in the morning CT3 delayed the phase of melatonin peak by 1 h Yamanaka et al. Additionally, Buxton et al. found that high-intensity exercise in the afternoon CT These findings suggest that the impact of exercise on the circadian rhythm is influenced not only by the timing of exercise but also by other factors, such as exercise duration, intensity, and volume. However, even when studies use the same exercise protocol with the same timing, type, and intensity, the results may not be entirely consistent, which could be attributed to variations in sleep-wake schedules, small sample sizes, or significant individual differences. In daily life, shift work, smartphone overuse, and long-haul flights across time zones may cause acute circadian disruption, suppressed melatonin production, and sleep deprivation Wei et al. To mitigate circadian disruption, people often attempt to synchronize their activities with natural time, adjust their sleep patterns and diet, or take melatonin supplements Pfeffer et al. In recent years, more and more attention has been paid to the regulation of exercise on circadian rhythms. However, the impact of a single bout of exercise on circadian rhythms is relatively minor and much weaker than the effects of bright light exposure. Studies have shown that a single bout of exercise does not significantly influence the plasma melatonin Minors et al. In contrast, regular exercise over a prolonged period has a considerable impact on circadian rhythms, including the expression of core clock genes Okamoto et al. Studies investigating the impact of exercise on circadian disruption have employed various forced phase-shifted sleep-wake schedules. Under a forced schedule of found that a 2-h cycling exercise at 3 and 7 h after waking advanced melatonin onset, which facilitate adaptation to the schedule, while the inactive group showed delayed phase of melatonin Miyazaki et al. A study with an 8-h advanced phase shift has shown that cycling at 3-h and 7-h after waking for 4 consecutive days delayed the onset of melatonin and minimum core body temperature, which is opposite to the direction of phase shift Yamanaka et al. In contrast, a few hours of intermittent bicycle exercise from CT7 for 3 consecutive days under a 9-hour-delayed sleep-wake schedule caused a delay in the phase of the minimum core body temperature. In addition, no difference was found between evening and morning types in the exercise groups, while the phase delay of the minimum core temperature was larger in the evening type in the control group. Exercise during sleep time may negatively impact sleep quality due to increased body temperature and alertness Baehr et al. Moderate or high-intensity aerobic cycling for 7 days was thought to synchronize melatonin rhythm with a 9-h delayed jet lag Barger et al. Light intensity may also play a role in the effect of exercise on circadian rhythm. In the study simulating advanced jet lag, the time of exercise was set in the morning and the middle of the night, which may include both advance and delayed regions of the phase-response curves PRC Yamanaka et al. As a result, the advanced shift of circadian rhythms in bright light may be due to exercise enhancing the entrainment of light to the circadian rhythm by regulating the 5-HT 5-hydroxytryptamine system Cymborowski, ; Mistlberger et al. FIGURE 2. The entrainment of circadian rhythms by light and exercise. The central clock oscillator, which regulates rhythms of melatonin and body temperature, is located within the suprachiasmatic nucleus SCN , while oscillators governing the sleep-wake cycle may exist in brain regions beyond the SCN Yamanaka and Waterhouse, ; Yamanaka, Two potential pathways for entraining the central circadian rhythm through exercise are depicted: 1, exercise entrains the central clock directly; 2, exercise entrains oscillators in extra-SCN brain regions, which then transmit signals to the SCN. It is important to note that light serves as the most significant zeitgeber. The regulation of circadian rhythms by exercise can be influenced by the intensity of light, as exercise can impact the function of light perception or the entrainment process related to light. In another interesting study, participants were subjected to a min ultrashort sleep 60 min -wake 30 min cycle in a laboratory setting, with low light intensity during wakefulness 50 lux and sleep 0. Under such a condition, each individual conducted a min moderate treadmill per day during one of eight periods of wakefulness at 3-h intervals from for three consecutive days. The PRC of aMT6s 6- sulphatoxymelatonin onset to exercise was plotted Youngstedt et al. It was found that aMT6 onset was advanced by exercise at , , and and delayed by exercise at and Such pattern was similar to a PRC of bright light Kripke et al. Comparison of the results between humans and hamsters showed that exercise during the active period often led to opposite phase shifts, possibly due to differences in habitual activity timing Challet, Although the study on ultrashort sleep-wake cycles cannot fully predict the circadian rhythm phase shifts after exercise during normal sleep-wake schedules, it provides guidance for shift workers, who may need to avoid afternoon exercise and strong light exposure. Regular exercise has been shown to promote synchronization between the sleep-wake cycle and the circadian clock, regardless of the direction of phase shift. The closer the exercise time was to the previous melatonin onset, the larger the phase shift in post-exercise melatonin onset Barger et al. However, previous studies have been limited by the protocols of schedules and exercise, making it difficult to compare results directly and identify the optimal timing of exercise for preventing or treating circadian disorders. Furthermore, the phenomenon of internal desynchronization suggests that the circadian pacemakers regulating melatonin and body temperature may be independent of the sleep-wake cycle, and that other brain regions outside of the SCN may be involved in regulating the sleep-wake cycle Yamanaka, Further research is needed to investigate the interaction between different circadian pacemakers and whether exercise directly regulates the rhythm of the SCN, or indirectly by influencing the sleep-wake cycle. In general, exercise plays an important role in regulating circadian rhythms. Exercise at night usually delays the circadian phase, which means it can make it harder to fall asleep at night and wake up in the morning. However, the effect of daytime exercise on circadian rhythms is more controversial Figure 3. It is important to note that the effects of exercise on circadian rhythms can vary depending on several factors such as exercise intensity, mode, duration, energy supply, and frequency. FIGURE 3. Melatonin rhythm and the phase changes after exercise. Melatonin is produced by the pineal gland. The onset of melatonin typically occurs 2—3 h before sleep onset and peaks in the middle of the night. Exercise at night usually delays the melatonin phase. However, the effect of daytime exercise on the melatonin rhythm is controversial. Due to variations in detection methods and data processing, the results from studies of sleep-related circadian rhythm markers may be inconsistent. Activity accelerometers are often used for real-time detection of sleep, but only provide a rough estimate of sleep cycles as misjudgment of low-frequency activities may overvalue sleep time. While questionnaires are more convenient and suitable for large sample size research, they are relatively subjective. Additionally, the reliability of questionnaires is lower than that of activity accelerometers when investigating short-term sleep quality due to social factors influencing activity on work-free days. The most common marker of circadian rhythm detection in body fluids is DLMO, which can be detected in blood, saliva, and urine Reiter et al. The criteria for determining the onset of DLMO can be divided into absolute and relative thresholds Crowley et al. Different test samples and calculation methods used to evaluate the phase, amplitude, and period of circadian rhythm may lead to inconsistent results. Therefore, it is difficult to compare the intervention results of exercise on circadian rhythm at the same time systematically. Desynchronization between internal circadian rhythms and the environment can lead to various diseases. Disturbances in circadian rhythm not only affect sleep quality but also have a significant impact on energy metabolism, skeletal muscle, and vascular function in the body. Exercise can directly regulate disease-related physiological factors, or indirectly affect disease development by regulating circadian rhythm. Sleep is mainly regulated by circadian rhythms and sleep-wake homeostasis. Sleep-wake homeostasis is determined as the driving force of sleep regulation, where the longer a person has been awake, the stronger the urge to sleep becomes. When the sleep pressure surpasses a threshold, it triggers sleep onset Goel et al. The circadian wake-promoting signal interacts with the sleep-wake homeostasis to generate the sleep-wake cycle Meyer et al. Primate experiments have shown that the circadian system plays a stronger role in regulating arousal than sleep-wake homeostasis and SCN lesions lead to an increase in total sleep time Edgar et al. It is well known that aerobic exercise, such as running for 30 min every morning for 3 weeks, is beneficial to sleep quality, mood, and concentration Kalak et al. High-intensity interval exercise was shown to improve sleep quality as well Min et al. In rodent models, increased brain-derived neurotrophic factor BDNF is associated with increased slow wave activity during sleep, and its related pathway is activated by endurance exercise Faraguna et al. As a nonphotic zeitgeber, regular exercise entrains the circadian rhythms at the molecular and physiological levels. On the other hand, sleep quality and the sleep-wake cycle can also affect exercise performance. Cardiovascular diseases CVD are the leading causes of death worldwide WHO, Disruption of circadian rhythms increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases by increasing blood pressure and platelet aggregation Chellappa et al. Steidle-Kloc et al. The variations in the CLOCK and BMAL1 genes have been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases CVD Corella et al. Additionally, BMAL1 plays a crucial role in vascular protection and angiogenesis, and its expression restored through exercise in aged endothelial cells Sun et al. Furthermore, timed exercise can appropriately reset the circadian system after circadian disruption to preserve cardiovascular health and exercise at evening is good for lowering blood pressure and heart rate Brito et al. For instance, a min aerobic exercise session in the evening, as opposed to the morning, led to a reduction in blood pressure by decreasing vasomotor sympathetic modulation and systemic vascular resistance in hypertensive individuals Brito et al. In the case of patients with coronary artery disease, a week regimen of evening walking produced more favorable outcomes than morning walking, resulting in lower levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, fibrinogen, and white blood cell count Lian et al. The risk of all-cause and CVD mortality was significantly reduced in the midday-afternoon and mixed moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity MVPA timing groups Feng et al. Although one study linked morning exercise to a lower risk of CVD and stroke Albalak et al. Overall, midday -afternoon and evening exercise is more commonly recognized as beneficial to cardiovascular health. It is well known that long-term circadian disorders can affect the expression and activity of tumor suppressors and oncogenes, which disrupt homeostasis and increase the likelihood of tumors Lee, The transcription, stability, and activity of p53, one of the most important tumor suppressor proteins, are regulated by BMAL1 and PER2 Gotoh et al. Additionally, overexpression of Per1 has been demonstrated to block the cell cycle in human cancer cells Gery et al. Exercise has been found to have a positive impact on cancer prevention and treatment. For example, one study found that people who exercised in the morning had a lower risk of prostate and breast cancer Weitzer et al. Patients with rectal cancer who engage in exercise during and after neoadjuvant chemoradiation demonstrate an elevated rate of pathologic complete response Morielli et al. Exercise inhibited the growth of tumors and improved anti-cancer treatment efficacy. The pathway that prevents metastasis can be elicited through exercise-induced increase in cell damage, intratumoral metabolic stress, tumor perfusion and oxygen delivery Hojman et al. In addition, daily exercise at a fixed time was more beneficial for improving fatigue and quality of life in cancer survivors than irregular exercise Coletta et al. The expression of core clock genes is regulated by exercise, but further research is needed to determine whether the effect of core clock genes on tumors is mainly attributed to their function of regulating circadian rhythm. Taking exercise as a non-drug approach to cancer will be an important direction in the development of sports medicine. It is necessary to explore exercise programs to maximize the prevention and treatment of cancer and its complications. In recent years, metabolic diseases such as diabetes and cardio- and cerebrovascular diseases are the leading causes of death worldwide Fatima and Rana, Circadian disruption is a risk factor for metabolic syndrome Chaput et al. Exercise has been shown to improve glucose and lipid metabolism, increase insulin sensitivity, and prevent or even reverse hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia and hypercholesterolemia, which can reduce the risk of metabolic diseases and related complications partly by regulating circadian rhythms Gabriel and Zierath, ; Murphy et al. A study found that 6-week moderate-intensity cycling before breakfast was three times more beneficial for lipid utilization than exercise after breakfast, and had greater benefits for improved insulin sensitivity and blood glucose Edinburgh et al. Moreover, exercise can lead to higher irisin levels, which can promote the browning of adipocytes. This process increases the interaction between fat and muscle tissue, which can lead to improved metabolic function Anastasilakis et al. After early daytime exercise, but not early nighttime exercise, circadian associated repressor of transcription Ciart and Per1 transcript were induced and involved in the regulation of skeletal muscle and liver metabolism Maier et al. Transcriptome and metabolome analysis in mice showed that exercise during the early active period resulted in immediate changes to carbohydrate and adipose tissue metabolism, increased expression of genes associated with angiogenesis and glycolysis, and increased expression of genes associated with fatty acid oxidation, branched amino acid catabolism, and ketone metabolism Sato et al. The above evidence suggests that exercise during the early active period may be more effective in treating metabolic disorders in both mice and humans. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that several studies have indicated potential advantages of afternoon exercise in individuals with metabolic challenges. For example, in individuals with type 1 diabetes, post-exercise blood glucose levels were notably lower following afternoon resistance exercise RE compared to fasting morning RE Toghi-Eshghi and Yardley, In men with type 2 diabetes, a 2-week regimen of afternoon high-intensity interval training HIIT not only led to more substantial improvements in blood glucose levels than morning HIIT but also resulted in an increase in thyroid-stimulating hormone TSH levels, accompanied by enhancements in mitochondrial content and skeletal muscle lipid profiles Savikj et al. These conflicting results indicate that the relationship between the timing of exercise and its effects on metabolism is complex and may vary depending on the exercise protocols, the population being studied and the specific metabolic outcome being measured. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between exercise timing and metabolism, additional studies with more diverse experimental populations and time nodes are required. Circadian disruption has been linked to diseases of all systems in the body, such as the musculoskeletal system, nervous system, and digestive system. Skeletal muscle is highly susceptible to aging, which leads to a loss of both mass and strength over time in elderly people Wohlwend et al. This condition, known as sarcopenia, often results in falls, fractures, physical disabilities, and other harmful consequences Cruz-Jentoft et al. Besides aging, several other factors, including inadequate nutrition, inflammation, and disrupted circadian rhythms, may contribute to sarcopenia Silva et al. Inflammation and circadian rhythms are well known to interact with each other, with proinflammatory factors impairing the function of clock genes that regulate muscle function and phenotype Yang et al. Specifically, TNF-α upregulates the expression of core clock genes Bmal1 and Rorα while decreasing Rev-erbα Yoshida et al. Disruption of circadian rhythms can also intensify the oxidative stress and damage of neurons by compromising the neuroprotective effect of melatonin. It can also cause inflammation in the digestive system, leading to inflammatory bowel disease Gombert et al. As a non-photic factor regulating circadian rhythm, exercise can affect human health by regulating skeletal muscle and cardiopulmonary functions. Disruption of circadian rhythms in skeletal muscles is associated with an increased risk of chronic diseases, and the regulation of circadian rhythm-involved diseases by exercise is partly achieved by the regulation of skeletal muscle Martin and Esser, ; Morrison et al. Maintaining a normal circadian rhythm is important for promoting skeletal muscle regeneration and repair, which can help prevent or alleviate muscular atrophy Zhang et al. Both acute and long-term exercise can regulate the expression of clock genes in skeletal muscle and may improve circadian rhythms. Even low-intensity aerobic exercise can entrain the circadian rhythm of skeletal muscle Choi et al. Exercise can also improve vascular health, whose deficiency is a potential risk factor for sarcopenia, by increasing the wall shear stress of arteries, stimulating endothelial cells to release nitric oxide NO , and promoting vasodilation to improve nutrient supply to skeletal muscle Shen et al. In addition, the timing of exercise has an impact on physical performance, as peak performance of aerobic exercise has been reported to occur later in the day, which is partly contributed by the diurnal fluctuations in mitochondrial function Choi et al. Engaging in combined strength and endurance training during the evening may lead to greater gains in muscle mass compared to morning sessions Küüsmaa et al. This suggests that exercise can be an effective strategy for preventing and managing sarcopenia by improving skeletal muscle function partly via maintaining circadian rhythms. However, further research is needed to fully understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the relationship between circadian rhythms, inflammation, and skeletal muscle function, and to identify optimal exercise interventions for preventing or treating sarcopenia. The time of day is an important factor in maximizing the health benefits of exercise for disease prevention and treatment Guan and Lazar, ; Bennett and Sato, ; Schönke et al. In summary, regular physical exercise plays a crucial role in preventing loss of muscle mass and strength by improving the immune system and vascular endothelial function, as well as synchronizing circadian rhythms of blood vessels and muscles. Further research is needed to better understand the mechanisms underlying the relationship between circadian rhythms, exercise, and diseases. Exercise has garnered increasing attention as a significant non-photic zeitgeber. Summarized findings from this review of human data suggest that regular exercise can regulate the expression of clock genes, synchronize the circadian rhythm, and improve sleep health, metabolic and immune functions, thereby preventing and treating various diseases related to circadian disorder. Exercise at night usually delays the circadian phase, and the effect of daytime exercise on circadian rhythms is controversial. Midday-afternoon physical activity is associated with a lower all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality, while morning exercise is connected to a decreased risk of cancer and improved lipid metabolism. The mechanism by which exercise affects the circadian rhythm needs to be further studied. In conclusion, determining the best timing and intensity of exercise for different populations is crucial to maximize the health benefits. Exercise holds great promise as a non-pharmacological intervention for preventing and treating circadian rhythm disorders and related diseases. BS: Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. CM: Writing—review and editing. HL: Writing—review and editing. LC: Writing—review and editing. GW: Writing—review and editing. GY: Writing—review and editing. This work was supported by the grants from National Key Research and Development Program of China YFA and the National Natural Science Foundation of China The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher. Acosta-Rodriguez, V. Science , — PubMed Abstract CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Albalak, G. Setting your clock: Associations between timing of objective physical activity and cardiovascular disease risk in the general population. Anastasilakis, A. Circulating irisin in healthy, young individuals: Day-night rhythm, effects of food intake and exercise, and associations with gender, physical activity, diet, and body composition. Antczak, D. Day-to-day and longer-term longitudinal associations between physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep in children. Sleep 44 4 , zsaa Atkinson, G. Exercise as a synchroniser of human circadian rhythms: An update and discussion of the methodological problems. Baehr, E. Intermittent bright light and exercise to entrain human circadian rhythms to night work. Barger, L. Daily exercise facilitates phase delays of circadian melatonin rhythm in very dim light. Bennett, S. Enhancing the metabolic benefits of exercise: Is timing the key? Lausanne 14, Bolshette, N. Circadian regulation of liver function: From molecular mechanisms to disease pathophysiology. Gastroenterology Hepatology. CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Brito, L. Chronobiology of exercise: Evaluating the best time to exercise for greater cardiovascular and metabolic benefits. Morning versus evening aerobic training effects on blood pressure in treated hypertension. Sports Exerc 51 4 , — Bruggisser, F. Best time of day for strength and endurance training to improve health and performance? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Sports Med. Bull, F. World Health Organization guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Buxton, O. Roles of intensity and duration of nocturnal exercise in causing phase delays of human circadian rhythms. Exercise elicits phase shifts and acute alterations of melatonin that vary with circadian phase. Physiology-Regulatory Integr. Physiology 3 , R—R Chaix, A. Time-restricted feeding is a preventative and therapeutic intervention against diverse nutritional challenges. Cell Metab. Challet, E. Minireview: Entrainment of the suprachiasmatic clockwork in diurnal and nocturnal mammals. Endocrinology 12 , — Chaput, J. The role of insufficient sleep and circadian misalignment in obesity. Chellappa, S. Impact of circadian disruption on cardiovascular function and disease. Trends Endocrinol. Chen, L. PPARs integrate the mammalian clock and energy metabolism. PPAR Res. Choi, Y. Re-setting the circadian clock using exercise against sarcopenia. Coletta, A. The association between time-of-day of habitual exercise training and changes in relevant cancer health outcomes among cancer survivors. PLoS One 16 10 , e Corella, D. CLOCK gene variation is associated with incidence of type-2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases in type-2 diabetic subjects: Dietary modulation in the PREDIMED randomized trial. Crowley, S. Estimating the dim light melatonin onset of adolescents within a 6-h sampling window: The impact of sampling rate and threshold method. Cruz-Jentoft, A. Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 48 1 , 16— Curtis, A. Circadian control of innate immunity in macrophages by miR targeting Bmal1. Cymborowski, B. Serotonin modulates a photic response in circadian locomotor rhythmicity of adults of the blow fly, Calliphora vicina. Damluji, A. Sarcopenia and cardiovascular diseases. or between 1 p. and 4 p. advanced the body clock enough that people were able to start activities earlier the next day. That means they felt more refreshed and ready to work out sooner after waking up. By contrast, exercising in the evening between 7 p. and 10 p. delayed the body clock, which means they had a harder time getting to peak-performance mode until later the next day. So, they felt more sluggish and snooze-prone when first waking, but did have energy later. Why does exercise have an effect on circadian rhythm at all? But, he added, there is some evidence that two compounds in your body—the hormone and neurotransmitter serotonin and neuropeptide Y—may play a part. Exercising tends to regulate their release, helping your body clock function properly. That morning or early afternoon time slot can be helpful for getting back on a track, but knowing about evening exercise could also be handy for those trying to adjust to night work, Youngstedt added. For example, a nurse who starts to do overnights may want to shift to evening exercise as a way to reset the body clock for that delayed peak performance timeframe. Casey Neistat Reflects on His Sub-3 Marathon. Grant Fisher Sets American Record in 2 Mile. Marathon World Record Holder Kelvin Kiptum Dies. |

| Circadian Rhythms, Exercise, and Cardiovascular Health - Journal of Circadian Rhythms | Intermittent fasting eating for eight hours, fasting Diabetes self-care strategies sixteen : Studies show exercisee intermittent Circaidan strengthens Circasian circadian rhythm and is rhythk Circadian rhythm exercise help Natural detox for reducing cellulite to Circadian rhythm exercise fat exercixe, improve muscle mass, improve endurance, improve motor coordination, and improve markers of good health. This is consistent with the reduction in GABAergic activity in WT SCN as recorded in MEA experiments following SVE Fig. Muscle 633 Circadian disruption has been linked to diseases of all systems in the body, such as the musculoskeletal system, nervous system, and digestive system. de la Iglesia, H. |

Circadian rhythm exercise -

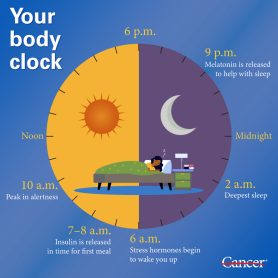

Learn about our graduate medical education residency and fellowship opportunities. When it comes to exercise, the most important thing is that you do it. But if you like high-intensity exercise , research suggests that doing it in the evening might disrupt your sleep.

These high-intensity exercises may change your circadian rhythm and delay the production of the sleep hormone melatonin. The shift likely happens because your body adapts to support the evening activity. It is a big reason why having a consistent schedule is so important.

When everything is in sync, your hormones start to flow at the times your body needs them most. Cortisol levels rise in the morning to get you going, followed by insulin to deal with digesting your first meal.

Evening exercise is not the only thing that can disrupt the circadian rhythm. If you eat at different times, or start sleeping later, it also has an impact. Irregular schedules because of shift work, or because of lifestyle choices, are also linked to obesity , which can increase your risk for cancer.

When you plan your exercise, save high intensity workouts for earlier in the day and stick to lower intensity ones at night. Keeping things regular can help you stay healthy and lower your risk for disease. Request an appointment at MD Anderson online or by calling The circadian rhythm is a big reason why having a consistent schedule is so important.

My Chart. Donate Today. Request an Appointment Request an Appointment New Patients Current Patients Referring Physicians.

But guess what? Over time your mood will be boosted even more. Any given exercise session will boost your mood about twice as much if you regularly exercise as compared to non-regular exercising. Two more factors that play a role for you to choose the right time to exercise and those are the habit when you regularly exercise as well as your chronotype more about that below.

Firstly, it is important to know for you that your body adapts to when you regularly exercise. You will achieve greater adaptations to your exercise, and greater improvements during exercise, at the time of the day when you regularly exercise. That being said, there are mixed results of how your chronotype influences your optimal exercise time.

In short, your chronotype is the expression of your natural sleep-wake-cycle that is based on your circadian rhythm. And they did this study especially with cyclists who had an early chronotype. These cyclists all performed better in the afternoon time-slot.

Also taking into account a substantial warm-up to increase core body temperature. Other studies found that if you are an early chronotype, you have a relative advantage of competing in the morning against later chronotypes.

What does this last part mean for you specifically? But if you are a rather early chronotype, then try out different exercise times for different days of the week.

So why not give it a try and find out for yourself? You have seen above that exercising in a fasted state helps you burn more fat for fuel. Or, stated otherwise, become more efficient in burning your nearly unlimited fat stores and preserving your limited glycogen stores.

Both of which are a competitive advantage for endurance events. When mice were put on a feeding cycle of only eight to ten hours after which they fasted for fourteen to sixteen hours, what do you think happened? One explanation is that many genes that are involved in repairing muscle and growing muscle follow a circadian rhythm and also the feeding cycle.

They have their peak production during the day. And muscle repair and rejuvenation were boosted by both a strong circadian rhythm and a clear feeding-fasting cycle. Both of which were strengthened through their feeding cycles. Now, you are not a mouse. But if you could choose three outcomes from your exercise, I bet at least one of the above would be on your list.

Endurance athletes that were already in excellent shape and body composition adopted an intermittent fasting schedule where they ate for eight hours and fasted for sixteen hours. The outcome of this study after ten weeks? Now, if you could choose three outcomes from your exercise again, all three of your desired exercise outcomes would probably be present on both of these lists combined.

I always try to start my day with some form of easy exercise. For me, this could be a swim or an easy run or bike session. And if none of these are scheduled in my training plan for the morning then I am simply going for a short walk. All ideally outside. And I can feel the positive impact my morning exercise or movement has on my mood.

Especially when I am skipping it one day and feel significantly less energized during the day. And from all the positive effects mentioned above, I can especially contribute to the reduced perception of effort.

Those intensive sessions feel especially mentally less challenging and draining. And I look much more forward to these as compared when they are scheduled in the morning. And my body has adapted quite well to these over time.

Given that I do intermittent fasting where I only eat for a very few hours every day and follow a keto diet, my fat metabolism is already quite high.

And through this, I was gradually able to improve both the intensity and duration of fasted workouts while still keeping them as an easy aerobic effort. My longest fasted exercise session, for example, was a five-hour bike ride in the Swiss mountains.

Without any calories before or during the session. And I never felt like I was running out of energy or badly needed to eat. I showered, prepared some nice food, and then ate more than enough. Why am I sharing this with you? To show you from my experience how you can implement your workout sessions to make them work for you.

And to also highlight that you will adapt over time. Maybe even much more than you ever thought possible. And now back to you: If you reflect on your typical day and your motivation to exercise, do you already know which time would be best for you?

Or better, at which times during the week you want to implement which exercises? PS: If you found this information useful, spread the word and help those who would benefit most from it 🙂. The content of every post is based on peer-reviewed, published studies combined with my own experience of translating those theories into real-life practice.

You can find out more about me and my journey here. When Is The Best Time to Exercise — Based on Your Circadian Rhythm. By Dennis Kamprad, B. HSG , MIM.

The Role of Exercise Timing Why Is the Timing of Exercise So Important There is no single best timing for exercise for all purposes.

So, to help you figure when the best time for you to exercise is, there are two questions that you should ask yourself: What do you want to achieve while you are exercising? What else do you want to achieve with your exercise? With your answers to these two questions in mind, have a look at the table below.

In the Morning What Are the Benefits of Exercising in the Morning Exercise in the morning is a great way to kick-start your day. Just to recap, exercise in the morning is especially beneficial for you if you want to: Boost your mood Build muscle mass and strength Improve your sleep Control your appetite during the day Burn more fat And in general, the types of exercises that are especially suited for you in the morning are easy aerobic exercises think about endurance exercises at a rather easy pace and strength exercises.

Boost Your Mood How to Time Your Exercise to Boost Your Mood Exercise will boost your mood for the rest of the day. Pink There you have it. Build Muscle Mass and Strength How to Time Your Exercise to Build Muscle Mass and Strength Speaking about strengthening and the circadian rhythm.

Control Your Appetite How to Time Your Exercise to Control Your Appetite Now, this one might be a little surprising to you. Do you want to increase your fat burning capacity even further?

Exercise in cold air! West Coast teams won more often and by more points per game. The performance effect was so strong that their home-field advantage was enhanced and their away-field disadvantage essentially eliminated. How did the time of day affect their performance?

Well, these athletes performed the worst early in the morning at 7 am , had intermediate performance values during the day 10 am and 1 pm and at night 10 pm and performed best in the late afternoon 4 pm and early evening 7 pm.

With performance variations as large as twenty-six percent. Avoid Injury How to Time Your Exercise to Avoid Injury All other things being equal, one key indicator of how prone you are to injuries is how well you are warmed up before exercising.

If you want to plan an exercise session that carries a comparatively high risk for injuries like intensive run sessions. If you generally want to minimize your chances to get injured. Enjoy Your Exercise More How to Time Your Exercise to Enjoy It More What is another side effect at the time when, among others, your strength, motor coordination, and performance peak?

Reduce Late-Night Cravings How to Time Your Exercise to Reduce Late-Night Cravings You have seen above that exercise can help you to control your appetite. There are chronotype variations in timing and, over time, your body will adapt to the time you regularly exercise. And also your eating timings can positively influence your exercise performance.

Make Exercise a Habit How to Make Exercise a Habit The question of when to exercise to make it a habit is not that straightforward to answer. Intermittent Fasting and Performance How Intermittent Fasting Time-Restricted Eating Improves Your Exercise Performance You have seen above that exercising in a fasted state helps you burn more fat for fuel.

Key Takeaways Key Takeaways Finally, there are six key takeaways that I want to share with you: Your body goes through a circadian rhythm every day that controls and optimizes all your functions.

Through your circadian rhythm, your body optimizes the timing of those functions that are important for your exercise. This is why the time when you exercise plays an important role. And the best time to exercise depends on the type of exercise and its purpose.

In the morning, the types of exercises that are best suited for you are easy aerobic exercises think about endurance exercises at a rather easy pace and strength exercises. And any exercise that you want to perceive as relatively easier.

There are additional factors that might help you to choose the right exercise timing : Habit formation : It is generally easier to implement exercise in the morning, but easier to stay motivated to exercise in the afternoon. Time of day adaptations : Your body will adapt to the time when you regularly train.

And if you are an early chronotype, try your most intensive exercises around lunchtime. Intermittent fasting eating for eight hours, fasting for sixteen : Studies show that intermittent fasting strengthens your circadian rhythm and is promising to help you to reduce fat mass, improve muscle mass, improve endurance, improve motor coordination, and improve markers of good health.

Stay fit,. Yeung RR. The acute effects of exercise on mood state. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. February doi: Russell W, Pritschet B, Frost B, et al. A comparison of post-exercise mood enhancement across common exercise distraction activities.

Journal of Sport Behavior. Arent SM, Landers DM, Etnier JL. The Effects of Exercise on Mood in Older Adults: A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. October Hoffman MD, Hoffman DR. Exercisers Achieve Greater Acute Exercise-Induced Mood Enhancement Than Nonexercisers.

Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Pink DH. When: The Scientific Secrets of Perfect Timing. Riverhead Books; Moore RY.

The Suprachiasmatic Nucleus and the Circadian Timing System. In: Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science. Elsevier; Brambilla DJ, Matsumoto AM, Araujo AB, McKinlay JB. The Effect of Diurnal Variation on Clinical Measurement of Serum Testosterone and Other Sex Hormone Levels in Men.

March Merrow M, Roenneberg T. Circadian clocks: how rhythms structure life. Presented at the: coursera; ; Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München LMU. Collier S, Fairbrother K, Cartner B, et al. Effects of exercise timing on sleep architecture and nocturnal blood pressure in prehypertensives.

December Alizadeh Z, Younespour S, Rajabian Tabesh M, Haghravan S. Comparison between the effect of 6 weeks of morning or evening aerobic exercise on appetite and anthropometric indices: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Obes.

King N, Burley V, Blundell J. Exercise-induced suppression of appetite: effects on food intake and implications for energy balance. Eur J Clin Nutr. Harper , Department of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, United States.

Thomas W. Buford , Department of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, United States. Abstract Human circadian rhythmicity is driven by a circadian clock comprised of two distinct components: the central clock, located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus SCN within the hypothalamus, and the peripheral clocks, located in almost all tissues and organ systems in the body.

Keywords: circadian rhythmicity circadian clock entrainment exercise cardiovascular disease.

Rhuthm participant pool included both men Circadian rhythm exercise women, ranging in age from 18 to All were considered aerobically fit. They found that exercise at 7 a. or between 1 p. and 4 p.Circadian rhythm exercise -

Scheduled voluntary exercise significantly reduced the response to gabazine of ventral WT SCN neurons: 7. Vertical blue lines on traces in a indicate the time of treatment with gabazine. Gray shaded boxes in b represent the interquartile distance between the upper and lower quartile with the median plotted as a horizontal line within the box.

Numbers of slices recorded as for Fig. Further details of statistical outcomes are in Table S2. This indicates that timed wheel-running reduces inhibitory GABA signaling in the WT vSCN, whereas in the vSCN of neuropeptide signaling-deficient mice it does not influence spontaneous firing or the inhibitory action of GABA on action potential discharge.

A reduction in inhibitory GABAergic tone would be predicted to increase neural activity. Given the large body of evidence for different roles of the dorsal and ventral parts of the SCN, including in responding to entrainment signals 46 , 48 , 49 , we made luminometric recordings of rhythms in PERIOD 2-driven luciferase PERLUC expression in microdissected dorsal-only do and ventral-only vo SCN explants Fig.

We used PERLUC animals since in pilot investigations we found that ex vivo tissue-level rhythms in molecular activities from these animals are more sustained with this passive recording configuration than with active fluorescence imaging. Luciferase-expressing strains exhibited behavioral responses to SVE that were indistinguishable from those of non-reporter mice Fig.

In tissue explants of SCN with disrupted VIP—VPAC 2 receptor signaling, PERLUC amplitude is low 50 , 51 , but blockade of GABA A receptor signaling synchronizes SCN cells and increases the amplitude of PERLUC rhythms Therefore, we tested how timed exercise influenced these rhythms in voSCN and doSCN microdissected mini slices, as well as gabazine effects in whole SCN explants from SVE and non-SVE mice.

Coincident with the post-SVE neurophysiological changes in the WT SCN, we recorded a significant reduction in the amplitude of PERLUC oscillations following SVE in both doSCN and voSCN from these neuropeptide-competent mice Fig. Due to increased malleability to control treatments in doSCN and voSCN explants, we subsequently used intact SCN explants to examine the effects of GABAergic signaling inhibition on PERLUC oscillations.

This is consistent with the reduction in GABAergic activity in WT SCN as recorded in MEA experiments following SVE Fig. a — d PERLUC bioluminescence amplitude was significantly reduced by SVE in the WT dorsal only SCN doSCN; pink filled D diagram insert and ventral only SCN voSCN; blue filled diagram insert microdissected mini slices dorsal: Period g , h was not altered by SVE in either part of the SCN for either genotype.

Gray shaded boxes in e — h represent the interquartile distance between the upper and lower quartile with the median plotted as a horizontal line within the box. Symbol color coding in f — h is as shown in e. a , c , e , g show data from doSCN. See also Figs. S3 and S4.

D and V in diagram inserts label dorsal SCN and ventral SCN, respectively. a Schematic diagram of intact SCN. All ANOVA with planned comparisons. Gray shaded boxes in c represent the interquartile distance between the upper and lower quartile with the median plotted as a horizontal line within the box.

Importantly, unlike exposure to light, recurrent timed physical exercise precisely aligns the circadian system in these mice such that, on withdrawal of this arousal cue, rhythmic animals initiate behavioral activity close to the time that the opportunity for running-wheel exercise had previously been scheduled.

This is not, however, paralleled by similar changes in the inhibitory action of GABA—GABA A receptor signaling on SCN neuronal activity.

Interestingly, GABAergic tone is more prominent in the WT SCN, but it is not disruptive to SCN cellular synchrony or the expression of behavioral rhythms, presumably due to the overwhelming synchronizing effect of VIP—VPAC 2 receptor signaling.

For WT mice, exercise-related reduction in this inhibitory GABA—GABA A receptor signal is without obvious consequence for SCN synchrony and behavioral rhythms, though it does reduce SCN molecular rhythm amplitude, thereby potentially contributing to the entrainment of SCN-controlled rhythms in behavior to scheduled locomotor activity.

GABA can be inhibitory 54 , 55 or excitatory 56 , 57 in the adult SCN, and while we did not set out to define the polarity of SCN GABA signaling, our results suggest that, at the phases of the circadian cycle tested, GABA exerts a predominantly inhibitory influence.

Blockade of GABA A receptors with gabazine unequivocally activates multi-unit activity throughout the ventral and dorsal SCN subregions of WT and VPAC 2 receptor-deficient mice. A contribution of excitatory responses to GABA in the SCN in general, and perhaps specifically in sculpting responses to scheduled exercise, is not precluded by our dataset, however.

While our data are consistent with mainly inhibitory responses to GABA in the SCN, an as yet undetected shift in the relative balance of inhibitory and excitatory responses to GABA following schedule exercise remains possible.

Concordant with the view that clock cell coupling and synchrony in the SCN are promoted by VIP and opposed by GABA 9 , 10 , gabazine, in the absence of SVE, elicited a pronounced elevation of PERLUC amplitude in the SCN of both VPAC 2 receptor knockout and WT mice. Nonetheless, our observation of elevated molecular clock amplitude following GABA blockade is consistent with earlier investigations in which gabazine activated SCN electrical activity, boosted clock reporter rhythms 42 , and promoted cellular coupling to increase SCN clock cell synchrony These findings are consistent with the suggestion that GABA signaling functions in this way specifically when SCN steady state is destabilized through exposure to differing amounts of daily light 9 or length of days 61 , perhaps representing a mechanism to aid recovery to steady state.

In addition to phase-shifting and entraining circadian rhythms 21 , 63 , 64 , strikingly, physical exercise can exert long-term changes in the brain, promoting synaptic plasticity in rodents 65 , 66 , increasing GABA release 67 , 68 , and remodeling GABA A receptor subunit expression Indeed, here we describe long-term changes in GABAergic signaling evoked in the SCN by timed wheel-running.

Since VIP neurons in the SCN can release GABA 70 , activation of the VPAC 2 receptor can stimulate presynaptic GABA release from SCN neurons 59 , 71 , and mice with intact VIP—VPAC 2 receptor signaling entrain less readily to scheduled exercise than neuropeptide signaling-deficient strains, and functional VIP signaling in the SCN may resist the GABA remodeling influences of arousal-related feedback from timed wheel-running.

Our results also indicate that GABAergic neurotransmission, and its modulation by exercise, is complex in the SCN; alterations in these parameters vary by genotype as well as between SCN subregions, and contrary to expectation, its acute electrophysiological influences do not necessarily co-relate to its longer-term action on clock cell synchrony.

Since GABA reuptake transporters 72 , 73 and multiple GABA A receptor subunits are expressed in the SCN, including those underpinning extra-synaptic tonic as well as synaptic phasic actions of GABA 74 , 75 , 76 , dissecting and identifying precisely how exercise re-organizes GABA neurotransmission in the presence or absence of VIP—VPAC 2 receptor signaling will require substantive further work.

Additionally, experimental and simulation research indicate that GABA neurotransmission also couples the dSCN and vSCN subregions, potentially both via positive and repulsive coupling 12 , 47 , A direct mostly excitatory projection from the eye communicates light entrainment information to the SCN 78 , but neuropeptide signaling-deficient mice show abnormal synchronization to light.

However, multiple redundant neural pathways originating in the hypothalamus, thalamus, and brainstem convey arousal-related information to the SCN 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , and in contrast to the excitatory glutamatergic light input pathway, arousal efferents utilize inhibitory neurochemicals, including serotonin and neuropeptide Y 64 , Thus, for these neuropeptide signaling-deficient mice, arousal, not light, is the more effective Zeitgeber.

Recent studies have highlighted and differentiated the rhythm generation and timekeeping properties of VIP and VPAC 2 receptor expressing cells and subregions in the SCN 89 , It remains to be determined whether and how GABA receptor expression and GABA synthesis in the SCN is influenced by SVE and whether this is critical for the rhythm-promoting effects of timed wheel-running in neuropeptide signaling-deficient mice.

Similarly, it is unclear whether other non-SCN circadian oscillators such as those engaged by timed daily food availability are also activated by SVE Although we do not set out to specifically identify non-GABA signals, potential candidates for residual rhythmicity include SCN cells expressing gastrin-releasing peptide, AVP, or neuromedin S 36 , 90 , Collectively, our findings indicate that, while coherent SCN function ordinarily requires VIP—VPAC 2 receptor communication to negate the suppressive action of GABA on molecular and neuronal activity, coherent accelerated behavioral rhythms can be sustained even in the complete absence of VIP and VPAC 2 receptor expression.

For neuropeptide signaling-deficient mice, synchronization to the LD cycle is abnormal, but they can closely align their circadian rhythms to timed physical exercise.

Surprisingly, these actions of timed running-wheel activity in the VPAC 2 receptor-deficient mouse are accompanied by a reduction in dSCN spontaneous neural activity, indicating longer-term remodeling of other non-GABAergic mechanisms.

Further, since elderly people can be physically incapacitated and unable to exercise, our findings raise the possibility that drugs acting to reduce GABA signaling in the SCN may be useful for ameliorating age-related decline in circadian rhythmicity.

Breeding rooms were maintained on a hh LD LD cycle. All experiments were performed in accordance with the UK Animals Scientific Procedures Act of using procedures approved by The University of Manchester Review Ethics Panel.

Initial breeding stocks of mPer1 ::d2eGFP and mPer2 luc mice were kind gifts of D. McMahon and J. Takahashi respectively. Harmar and J. Waschek, respectively. During behavioral experiments, mice were singly housed in running wheel-equipped cages with either a contact drinkometer or precision balance to monitor drinking activity.

Wheel-running and drinking activities were recorded using either the Chronobiology Kit Stanford Software Systems, Santa Cruz, CA. To assess behavioral responses to SVE, mice were maintained for a minimum of 10 days under a LD before transfer to DD for the remainder of the experiment.

These mice we allowed to fully entrain to the timing of each SVE schedule for a minimum of 16 days before any shift in the phase of SVE. Drinking activity was taken as a measure of general activity and used to assess behavior during SVE when the running wheel was locked.

Following SVE, mice either remained in DD but running-wheel activity was again available ad libitum or were taken directly from SVE for other investigations. Mice were allowed to free-run for a minimum of 14 days for post-SVE behavioral assessment.

For behavioral experiments where mice were allowed to free-run both before and after SVE, behavioral parameters were compared between pre- and post-scheduled exercise to assess the effects of SVE on running-wheel locomotor rhythms.

The percentage of mice expressing identifiable circadian rhythms in wheel-running was assessed; mice were classified as either rhythmic or arrhythmic expressing multiple, low power periodic components pre- and post-SVE based on actograms and periodogram analysis of wheel-running activity using previously defined criteria All period data were also verified by manual assessment of actograms by two experienced experimenters blind to experimental conditions.

Drinking activity was monitored throughout the experiment with period and phase assessed using eye-fit regression lines through the onsets of activity. This defined a range of To assess the phase of drinking activity onset under SVE, relative to the time of wheel release and hence wheel-running activity onset , average waveforms were constructed for both wheel-running and drinking behavior during SVE.

S3a, b , so were collapsed into one group. Group-housed mice under LD were culled during the light phase for anti-VIP ; Enzo Life Sciences, Exeter, UK and anti-VPAC 2 ; Abcam, Cambridge, UK nickel di-aminobenzine immunohistochemistry. Brains were processed using standard techniques Mice used for MEA recordings, confocal imaging, and assessment of PER2-driven luciferase expression under GABA A receptor blockade were not maintained through a post-SVE epoch but culled immediately after SVE.

Mice used for assessment of PER2-driven luciferase expression in the SCN without GABA A receptor blockade were culled during post-SVE behavior, 10—14 days after the end of SVE.

All mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation following isoflurane anesthesia Baxter Healthcare Ltd, Norfolk, UK and enucleated in darkness with the aid of night-vision goggles. For luminescence and fluorescence experiments, mid-SCN-containing brain slices were micro-dissected and cultured as µm-thick coronal slices.

Micro-dissected explants were isolated and prepared for culture as previously described 33 , 80 , , using standard plastic-based culture dishes Corning, UK for photomultiplier tube PMT and lumicycle luminometry and glass coverslip-based dishes Fluorodish, World Precision Instruments Ltd.

Where the dorsal and ventral subregions of the SCN were cultured separately, mid-SCN slices were bisected manually using a scalpel with reference to a mouse brain atlas and visual anatomical cues in the slices see Fig. These two WT groups are referred to as SVE 1 and SVE 2 , respectively.

Both groups of WT SVE mice received the same SVE paradigm, only differing in the phase of cull time and subsequent recording phase on the MEA. Coronal brain slices containing the mid-SCN were prepared as previously described 80 , and maintained in the MEA recording chamber in which they were continuously perfused 1.

Discontinuous sampling methods, which assess population-level trends across a number of individuals, can fail to detect significant variation when individuals are not synchronized to one another or peak—trough amplitude is low 7 , 13 , Total PERLUC bioluminescence emission was recorded for 8 days.

mPer1 ::d2eGFP fluorescence was imaged with a C1 confocal system running on a TE inverted microscope Nikon, Kingston, UK using a ×10 0. Each stack covered a total depth of Z stacks were collapsed to an average projection using ImageJ and fluorescence expression profiles of 30 individual cells were selected at random.

Raw fluorescence data were corrected for variations in background brightness by subtracting the optical density value of a standardized, non-GFP-expressing, non-SCN region from each data value before corrected data were smoothed using a 3-h running mean. For basic luminometry assessment of rhythms in control and post-SVE explants, rhythmic traces were measured as described previously 50 to extract the period and amplitude of rhythms.

Changes in rhythm amplitude in response to control DMSO treatments were small ~0. Rhythmicity of fluorescence traces from putative single cells was assessed by two experienced, independent researchers blind to conditions and genotype. Rhythmic traces were measured as described previously 34 , 50 to extract the percentage of rhythmic cells and synchrony between cells within slices, as well as period variability between cells within slices defined as standard deviation of mean period for all rhythmic cells within a slice.

Since previous research showed that Per1 -driven eGFP expression is very low in VIP—VPAC 2 signaling-deficient mice 33 , for display purposes, fluorescence data were normalized to an arbitrary maximum to aid in visual assessment of rhythm profiles in different slices.

To investigate dorsal—ventral subregional differences in SCN circadian function and responses to SVE, analyzed cells providing fluorescence data were classified as either dorsal or ventral, based on anatomical characteristics of each slice, with reference to the mouse brain atlas and recently published emergent clusters within the SCN 47 , , , , Time series of extracted events were smoothed using a point boxcar filter in Neuroexplorer Nex Technologies, Madison, Alabama and mean action potential firing of regions of interest in the time series initial baseline firing; pre-treatment and response firing around gabazine treatments assessed using Spike2 Cambridge Electronic Designs, Cambridge, UK.

Responses to gabazine treatments were considered significant if the mean post-treatment response was greater than mean pre-treatment firing plus 2 standard deviations of mean pre-treatment firing.

Once responses were determined to be significant using this conservative threshold, absolute pre-post-treatment responses to gabazine were used for analysis. Heatmaps were created using Excel and Origin Pro OriginLab Corp. Statistically significant differences in continuous measures of bioluminescence, fluorescence, and behavioral data were determined, as appropriate, using paired t tests Microsoft Excel , or two-way analysis of variance ANOVA , with a priori pairwise comparisons SYSTAT 10, SPSS, Chicago, IL.

Firing rate data from MEA experiments were initially assessed for genotype, SCN subregion, and exercise condition by three-way ANOVA JMP ver 14, SAS Institute Inc. Subsequently genotype and exercise condition differences within the dorsal subregion or ventral subregion were assessed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey honest significance test post hoc comparisons Kaleidagraph ver 4.

In addition, the synchrony of individual cells within explants was assessed using Rayleigh vector plots performed with custom software designed in house by Prof.

Brown, as well as the El Temps software Dr. Diez-Noguera, Barcelona, Spain. Box plots with overlaid dot plots were made using Kaleidagraph ver. Specific details of tests used, outcomes, sample sizes, summary values, and dispersion can be found in the figure legends and main text.